Audiosurf Break My Mind

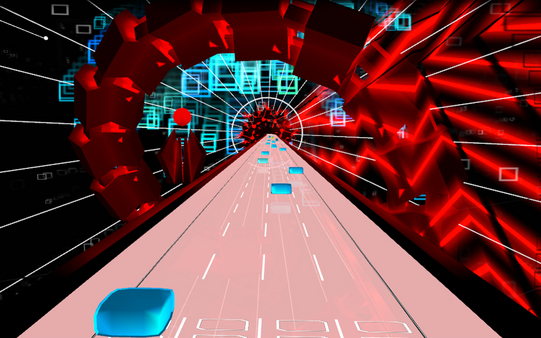

To be sure, there is no shortage of games that take your music and render it as a game. But Audiosurf manages to do something a little more intimate. You don’t just play a game based on your songs. You play your songs. It doesn’t just render the songs visible. It render them tangible. The ups are ups.

The downs are down. The louds are loud and the gentles are gentle. You don’t just see your music in Audiosurf; you feel through a sensation less like listening and more like dancing.If the above paragraphs didn’t make it obvious, I am something of an Audiosurf evangelist. I’ve spent more hours playing Audiosurf than Fallout 3. I want people to understand it. I want people to love it. I want people to realise it is not just another music game.

Audiosurf is a test of yourself, of the person you've become over these. And speed-ups and speed-downs and crazed drum-breaks and bass. Always on my mind, In my heart In my soul Baby Chorus: You're the meaning in my life You're the inspiration You bring feeling to my life You're the inspiration Wanna have you near me I wanna have you hear me sayin' No one needs you more than I need you And I know, yes I know that it's plain to see We're so in love when we're together.

To that end, I find myself regularly recommending songs to people that I think show off Audiosurf’s true potential. But Audiosurf’s pleasures are as varied as music itself.

Slow songs are as enjoyable as fast songs even if they offer an entirely different ride. There is no single song that can encompass the full spectrum of pleasure that Audiosurf allows. Instead, I have devised a mixtape. A playlist of ten songs that demonstrate just what Audiosurf does. I want to give this mixtape to you.Unfortunately, I can’t really give you the songs themselves, but I’ve tried to use well-known enough songs that you should be able to easily track them down.

For the full experience, put copies of all the songs in the one folder so that you can just click “next” at the end of each song (sadly, Audiosurf lacks any custom playlist feature). Though, don’t fear if you cannot track down copies of all these songs. Any of them by themselves is just as worthy of your time, and hopefully they will lead you to a whole new appreciation of just how magical this game is. And then, halfway through, just as you are getting relaxed, everything explodes.

The road plummets you down through a red tunnel of guitar distortion. The traffic here is so busy that you will be focusing more on staying alive and not overfilling your grid more than actually collecting points.But then you are at the bottom, the song is quiet again, and you are out of breath. The final uphill climb gives you a chance to clear the board and come to terms with what just happened. Now you’ve been tossed around. Now you are ready to play Audiosurf.

“It’s Not Meant To Be” – Tame Impala (Found on Innerspeaker)Audiosurf is not just about the uphill and downhill smooth rides. Some rides are jagged and bouncy. The entirety of Tame Impala’s Innerspeaker, for instance, is a wall of psychedelic guitars, cymbal crashes, and chamber vocals that have you bouncing over jagged roads and wheeling around corkscrews.

It’s an inertia-inducing ride. Particularly, the album’s opening track, “It’s Not Meant To Be” is something you must experience. You know you are in for something special the first time a sidewards corkscrew drops you straight down.Also surf: The entire Innerspeaker album. “Right Here Right Now” turns Audiosurf into what can only be described as a pointy-nippled rollercoaster (no really, look at the map). The initial build is slow and smooth as the chain cranks you up the first hill. The traffic fills quickly as the song ups towards its first salvo and then BAM you are over the first peak and bouncing down the first lot of whatever it is that voice is saying.

Let’s go with “Ain’t nothing fine. He loves my rail.” That’ll do.Then the cymbals (or something that sounds like cymbals) come in around the three minute mark as you continue to fall, each bringing its own short tunnel. Then you are at the bottom and ready to start climbing all over again. Take a breath. You’re only halfway.The climb begins again with another salvo of “Ain’t nothing fine. He loves my rail.” And smooths out into the synth-violin-ish rhythm again. The climb is fast and steep and you just know you are about to be dropped.

Another lot of “right here right now right here” fades out into echos for the steepest climb for a fraction of a second before what I can honestly say is one of my favourite moments of any game ever. You go over the second spike and fireworks! The steepest damn drop you will ever experience! You go down and down and down and, if you are anything like me, you are saying “Oh god,” under your breath repeatedly as you do so.The pacing is perfect, taking just enough time to pick you up before it throws you down. And then the song ends with a slow uphill climb to give you a chance to clear the board. There is an awkward spoken word section meant to introduce the album’s following song, “The Rockafella Skank” which doesn’t quite fit, but does give you a chance to calm down and find your Ventalin inhaler.Also surf: The entire You’ve Come A Long Way Baby album. “Skinny Love” – Bon Iver (Found on For Emma, Forever Ago)After Fatboy Slim, you might need a bit of a break.

Fortunately, because Audiosurf channels the songs themselves and doesn’t simply use them as a base for some other type of gameplay, it works with practically all styles of songs—including slow songs. Case and point: Bon Iver’s calm, beautiful, guitar and ghostly voice work just as well as the fastest house song.

The uphill ride is equal parts relaxing and haunting with the chorus picking up with the smallest, swiftest hills with Iver’s heartfelt cries. There isn’t much else to say about this.

It just works. “Casimir Pulaski Day” – Sufjan Stevens (Found on Come on!

Feel the Illinois!)Another slow song. The most difficult part of Stevens’s slow ballad about being in love with someone dying from cancer is seeing the road through your tears. I had listened to this song dozens of times before I surfed it, and it had never gotten to me.

But surfing it, being that intimately focused on its guitar plucks and Steven’s restrained, poetic observations hits you with the full power of its candidly-presented lyrics. The words travel through those little coloured blocks and get beneath your skin. The brief trumpet instrumentals quicken the pace and give you a moment to blink the water out of your eyes before the next verse. Then there is something in the background on the exact line where the person dies. I don’t know what it is, but it quickens the ride just enough to punch you in the face.And then the song ends on a surprisingly positive note with the choir and the trumpets and the “da-da DA da”s.

You slide over the hills as though you are surfing right into heaven. It’s sad, sure, but it’s beautiful.Also surf: “Chicago”6. “Bad Romance” – Lady GaGa (Found on The Fame Monster)Okay. That was a downer. Let’s pick it up a bit now for the second side of this mixtape.In the shopping centre I used to work in, they would play the worst pop music. But every time a Lady Gaga song came on I thought, “This would be great in Audiosurf.” And it is!“Bad Romance” has three peaks, each steeper and further downhill than the last.

The beat feels a bit slow and steady to be almost off-putting but the escalation of the song and the fanfare of the chorus keeps it interesting, as does the build up to the third and final act. Leave your skepticism at the door. You don’t have to enjoy listening to a song to enjoy surfing it.7. “Blue Monday” – New OrderThere is something skeletal about New Order’s “Blue Monday”, as though the flesh has been stripped back from the instruments’ noise. Every clank, beep, and drum is rendered so sharply by the game. This ride is jagged, off-putting, and unreliable. It starts you then it stops you.

It jerks you. It bounces you over paths bumpier than the main street of Springfield.

This is the song to ride if you want to see the formula of Audiosurf laid bare. Every sound of this song is so dissonant and jarring that it stands out more than it melds together.Mind you, it is not an easier surf. The road is packed with traffic from the get-go as the machine-gun drum bursts introduce the song and rarely go away. The stop-starting will throw off your rhythm and timing, too.

And it’s long, coming in at over seven minutes with almost no uphill breathers. This song needs your full attention. If you blink, you will overfill.Also surf: “Crystal”8. “Hearts A Mess” – Gotye (Found on Like Drawing Blood)It feels weird to say that a song surfs just like its film clip, but that is precisely how Gotye’s “Hearts a Mess” surfs like. In the film clip, large creatures with spindly legs walk around a world, kind of bobbing up and down with the song’s hallmark guitar plucks. When you surf it, you feel as though you are one of these creatures; going up and down over these hills is just your head bobbing as you step with your giant, spindly legs. It feels less like surfing and more like strutting.And then there are the drops during Gotye’s howls, as though you are surfing right down his throat.

Overall, a relaxed yet eerie surf.Also surf: The entire Like Drawing Blood album.9. “Teardrop” – Massive Attack (Found on Mezzanine)What is there to say about Massive Attack’s “Teardrop”? You know the song. You can probably guess exactly how it surfs.

It’s slow, relaxing, beautiful, and haunting. Most of the song consists of quick, shallow dips from one drumbeat to the next. Really, there is nothing else to say about it.Also surf: “Angel”10. “Juanita/Kiteless/To Dream of Love” – Underworld (Found on Second Toughest of the Infants)Finally, what better way to close proceeding than with a sixteen-minute electronic epic. The thing I love about Underworld is their songs have movements. That is, there are sections of their songs that are clearly distinct from the other sections, yet they are bridged so subtly and perfectly that you rarely notice the shift from one to the other until it has already been made.

This makes them a very interesting band to surf as the road can shift and change drastically beneath your surfer.“Juanita/Kiteless/To Dream of Love” has roughly three movements, as the name suggests. The first is a very gradual, steady, traditional climb and drop. The traffic builds and builds until the road is utterly crowded with keyboard tones and cymbal crashes. It can be a hard path, getting through it alive, but if you survive this you should survive the rest of the song.The first act shifts into the second roughly around the bottom of the first hill via this distorted pseudo-guitar rhythm starts playing over the beat.

This section plays straight and bumpy, like staccato heartbeat monitor.The third act starts with a large but busy uphill climb before Act Two returns with a vengence in a downhill clash of noise towards the finish line. Then, finally, the song fades out over a good 90 seconds, giving you ample time to clear the board.Also surf: Every song by Underworld ever.And that is my Audiosurf mixtape, for you. I hope you like it. By no means is this an exhaustive list of songs worth surfing. A good mixtape gets the listener into new bands that they then go off and discover for themselves.

Hopefully this does the same for your audiosurfing. These are the kind of rides awaiting you. Go out and find some more.

The games industry is a very broad artistic church. From architecture to sound engineering, almost every artform is virtually represented in some way, and all at various stages of evolution.

Although many games can’t manage to tell a story more complicated than, by comparison gaming’s orchestral scores and electronic soundtracks are held in the highest regard.It’s fair to say that gaming’s contribution to music is one of its biggest success stories. These days, videogame music is played in concert halls around the world, and its creators are some of the most respected people in the industry.

But what exactly is music’s contribution to gaming? After all, music is not a fundamental component in the development of a game, insofar as the game will continue to function without it. Yet the pervasiveness, quality and success of videogame music indicates it is more vital than may initially be apparent. So what can we learn from music’s influence on gaming?

How does it affect the player’s experience? And to what extent can it influence the way games are created? To answer these questions, I spoke to three members of the games industry who have tackled the relationship between music and videogames in very different ways. Is one of the game industry’s best known composers, having written music for the first two Mass Effect games and the likes of Unreal II and the Myst series prior to that.

He is also the co-founder of Video Games Live – the touring concert event which had its debut in 2005. Currently working on the score for Black Ops 2, Jack believes that music plays a crucial role in the development of storytelling in games. “Music is the unseen character.

It's the emotion behind the actions of the player. It's gently there to show the game designer's intention. It's totally collaborative with the developer.”. “This is the relationship between music and games that we are probably most familiar with. Music can be used to accentuate the actions of the player, to provide certain emotional cues and communicate the tone of the current level or scene. In some ways this scoring of a game is similar to creating music for a film, designed to run in concurrence with the events being played out on the screen.

But even the most directed games must take into account one massive variable: the player. With a complex game like Mass Effect, this can include how long a player is in a particular area, transitions between peaceful and combat situations and the choices the player can make. “It's really not until I start to see gameplay that I truly know what to do with the music,” Jack says.

“As soon as I see a decent rendering of a level I can get a beat on what the music should do.” Interestingly though, music does not always follow the pace of the game. Sometimes the opposite is true. An example of this is Minor Spoilers from Mass Effect 2, composed by Jack before this part of the game was developed: “Casey Hudson came to me fairly early and said, ‘I'd like you to start by writing the end music for the game. Spoiler There's going to be this suicide mission and I want it to feel like you're taking your team and rushing in to save the universe’. He was giving me permission to write a truly kick-ass piece of music.

No visuals and no timing. He wanted to get the music done so that when he was piecing the ending together, he'd be listening to that piece of music.” When music begins to directly influence not just how a game is experienced, but how a game is actually created, things become really intriguing. Sometimes music can be the basis upon which entire games are built. Since the advent of home and commercial computing, it has been possible to break down digitised music into its component parts. The resulting information can be used in the creation of levels and environments – and the most successful example of such a game is 2008’s musical rollercoaster. ““A big part of it was just wanting a better music visualiser,” says Dylan Fitterer, Audiosurf’s creator.

“There were a few I enjoyed, but they quickly became boring and my mind would wander. I wanted one that could create a better listening experience by focusing my attention on the music.” The path to creating a more engaging music visualiser involved making it interactive, compelling the player to react to something directly linked to the music. Audiosurf further differentiates itself from standard music visualisers in more fundamental ways, as Dylan explains.

“It analyses the entire song before the player starts listening. This way Audiosurf can visualise not only the music as it happens, but also the music's future. Players can see the music coming to heighten their feeling of anticipation.” Audiosurf approaches music from the opposite direction of Mass Effect. Whereas Jack creates music for games, Dylan has created a game for his music. At the same time, however, both games share a striking commonality, which Dylan goes some way to explaining.

“I'm excited to have found a tight relationship between gameplay and music. Because it's a game, Audiosurf is a better music visualiser.

Gameplay goals serve to focus the player completely on the music. Because it's a music visualiser, Audiosurf is a better game. Replayability is my most important ideal in game creation, and music gives Audiosurf unlimited replay.” Here we have a conceptual feedback loop in which the music and the game complement each other.

Music becomes more powerful, more evocative, when the listener is involved in an activity linked directly to it. Siren cast. In turn, those actions that become associated with the music are themselves heightened. This applies equally to Mass Effect and Audiosurf, even though these games implement music in very different ways.

“One man who has put considerable thought into the theoretical similarities between gaming and music is, the co-developer behind the upcoming maverick indie title. “Many of us are not accustomed to perceiving the time-structures (rhythms/forms) of videogames as musical,” David says. “They are often freely or procedurally rhythmic and can have strange formal structures, all emerging from the player’s inclinations. These rhythms and forms tend to more closely resemble free jazz and other improvised music than they do the film scores or pop forms that a lot of game music takes its inspiration from.” Proteus strips away many of the conventions we have traditionally come to associate with videogames, foremost amongst which are a predetermined challenge or objective, and the ability to directly interact with the environment. Interaction is only possible through the game’s music, which changes dynamically depending on the player’s location, the time of day, the season, and so on. Every tree, animal, and building emits an individual noise, the sounds gradually layering themselves as the player explores the game’s islands.

“Music in videogames can be so interesting because you’re creating a musical space, a field of possibilities, rather than a musical script. This allows the composition process to be infused with improvisation/play at all times, even as a final product.

And because of how the computer is good at handling data, and manipulating it, it’s possible to delineate the boundaries of the spaces in dynamic ways that haven’t really been possible until now.” Proteus sits somewhere in the between Mass Effect and Audiosurf in terms of how it plays with music. Like Mass Effect, the music alters depending on the actions of the player, but at a layered, note-by-note level rather than in specifically composed chunks. And like Audiosurf, the music is directly related to the layout of the level, except the relationship is inverted, so the movement of the player dictates how the music evolves. This results in a curious psychological effect where the player is encouraged to explore and experiment without any direct instruction.